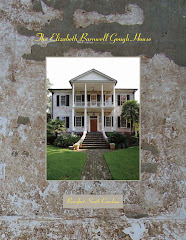

It is a history as richly patina-ed as the tabby walls of its exterior. Extraordinary people came, lived and died here. Ordinary people have added to its history as well. There were people of great wealth and people who struggled with economic hardships. There were people who helped shape their eras and people whose lives were shaped by their times. Their stories tell the history of Beaufort and a much larger one that I will begin to share with you in exerpts from my research and writing for the owners of this remarkable home.

Traditionally, the history of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House begins in 1775 with the death of Elizabeth’s father Nathaniel Barnwell. The eldest son of Tuscarora Jack Barnwell, Nathaniel had amassed a sizable fortune, 1600 pounds of which he left to his daughter Elizabeth. The legacy provided for her lifetime support and for her daughter’s until Marianna’s marriage in 1791. The legacy also enabled Elizabeth to build one of Beaufort’s grandest and most beautiful homes.

But in a broader sense, the history of the Elizabeth Barnwell House begins long before the legacy or the home’s construction.

It can be argued that the history of the house begins even before Elizabeth’s birth with the remarkable life and achievements of her grandfather, Tuscarora Jack Barnwell. (More about Tuscarora Jack in my next blog.) Though he died 29 years before her birth, he left a legacy of bold action and independent spirit that shaped the character of the Barnwell family and undoubtedly played a large part in making Elizabeth who she was, the choices she made in life and even in the commanding presence of her home.

Elizabeth’s story, like her grandfather’s, is a colorful one. In fact and legend, it is one of Beaufort’s more intriguing tales. At 18, Elizabeth Barnwell had attracted the attention of 21-year-old James Island planter, Richard Gough. At the time, the Barnwell family already had numerous ties with Charleston area society. Elizabeth’s mother was the daughter of a planter from neighboring John’s Island as was her brother Nathaniel II’s wife. Her aunt Anne’s first and fourth husbands and her aunt Katherine’s husband were all John’s Island planters.

Richard Gough would most certainly have been well known to Elizabeth’s family, who responded to his overtures by objecting to the match. Elizabeth’s family is said to have considered him “dissipated.” There may also have been concerns about his temper, which would later prove to be violent. To discourage the attachment, the family sent Elizabeth to London in the company of her aunt and uncle, her mother Mary’s brother John Gibbes and his wife.

Richard Gough followed her to London and the couple eloped to Greta Green. The town, just across the English border in Scotland, had laws between 1754 and 1856 that permitted hasty marriages and was notorious as a destination for eloping couples. On their return Elizabeth’s uncle, John, insisted on a church wedding and they were married again in London in May of 1772.

Elizabeth’s act of defiance in marrying Richard was not a singular event in the spirited Barnwell family. Her uncle, John Barnwell, had eloped with his mother’s ward Elizabeth Fenwick. A cousin, Ann Perroneau, left her husband to “elope” with the married Governor of South Carolina, Thomas Boone. Elizabeth marrying against her family’s wishes was nevertheless a daring act for a young woman of her time and one with unfortunate results.

The couple returned to James Island from London that August. The following year, on March 1st, 1773, their only child and daughter Marianna was born. Two months later, Elizabeth took her daughter to Beaufort never to return to Richard Gough. Accounts vary as to the cause of the sudden and permanent rift. One account places the blame on the couple’s fiery tempers. Another places it on her family. Hearing that Elizabeth was unhappy, they are said to have sent a boat for her and then stood in the way of her return to James Island. According to Elizabeth, the estrangement was perpetuated by her family’s refusal to consider a reconciliation. Their stand actually may have been in her best interest, for other credible accounts paint a disturbing picture of Richard’s character.

One such account maintains that when Elizabeth left for what she considered only a visit with her family in Beaufort, Richard in a pique of wounded pride had a housemaid gather up all Elizabeth’s belongings and sent them to Beaufort with the message that she was not to return. When Elizabeth, according to the law and custom of the time, petitioned the court to have Richard pay for her support as his wife,1 Richard at first agreed but later became violent, assaulting Elizabeth’s counsel and fighting a duel with the counsel’s nephew. Elizabeth, fearful that someone would be hurt or killed on her account, withdrew her petition. Richard Gough’s last will, dated 1791, gives further evidence of an angry and spiteful character. From an estate valued at 15,000 pounds sterling, he left just 50 pounds to Elizabeth, stipulating that it was in lieu of her dower. Another 50 pounds he left to Marianna, referring to Marianna as “her” daughter, not “our” or “my.” After his death, Elizabeth was able to sue for and regain her rightful dower, substantially more than the nominal sum Gough attempted to leave her. She also petitioned for the back alimony denied her by Gough. Her request, however, was refused as a personal claim that had died on the death of her husband in February 1796.

Fascination with the history of the couple has led to a number of other stories being passed down through the generations. One tale has Elizabeth’s younger brother Edward and Gough fighting a duel. Another tells of Elizabeth’s brother John passing Richard on the street in Charleston, each placing his hand on his sword as the only acknowledgement of the other. Yet another story has Richard Gough noticing a beautiful young woman in a shop in Charleston. When he inquired as to her identity, he was told that she was his own daughter, Marianna.

Whatever the reasons were behind the couple’s estrangement, Elizabeth and her daughter initially lived with her family until her father’s death in 1775 and in all likelihood until the end of the Revolutionary War. Although her inheritance from her father gave her the means to build a home, building in Beaufort would have been virtually impossible in the town during the war.

Until her home could be built, Elizabeth may have lived with her widowed mother and younger sister Sarah, eleven years Elizabeth’s junior. We know that her widowed mother and Sarah spent the war years living in the “Big House” built by Nathaniel Barnwell in Beaufort on the bay. Another possibility is that Elizabeth and Marianna lived with her brother Nathaniel II.

Nathaniel, a semi-invalid since suffering exposure as a boy during the Cherokee War, was made guardian of Elizabeth’s inheritance in their father’s will. Nathaniel had inherited their father’s Parris Island plantation known as “Old House.” His wife, also named Elizabeth, is believed to have died shortly after the birth of the couple’s third child, William, in 1774. His other surviving child, Nathaniel III, was born in 1772, making his two sons close in age to Elizabeth’s daughter Marianna. It is possible Elizabeth spent the war years rearing the three young cousins together.

It is unlikely that Elizabeth lived with any of her other immediate family members. Her other brothers John, Robert and Edward were all actively involved in the war and her only other surviving sibling, Anne, was married to Gen. Stephen Bull, one of the main targets of British reprisals during the Revolution.

By the war’s end, Elizabeth, at thirty, was the survivor of nearly a decade of upheaval. The years immediately following the Revolution, however, were marked by more than just the work of recovering from the devastation. A new nation was being built. Beaufort was on the verge of an all-new and highly profitable economy based on cotton. And Elizabeth’s family was at the epicenter of the social, economic and political rebirth taking place.

Following the war, the Barnwell family through marriage added an even longer roster of prominent names to the family tree that already included Berners, Stanyarne, Reeve, Stuart, Gibbes, Sams, Bull and Elliot. Her sister Sarah married James Hazzard Cuthbert. Her brother John wed Anne Hutson. Brothers Robert and Edward married sisters Elizabeth Hayne Wigg and Mary Hutson Wigg. In subsequent generations, the intermarriage between branches of the family would further solidify Barnwell power and wealth.

As the Barnwell family grew during the second half of the 1780s, so did its political influence. In 1788, all eight of the delegates sent by South Carolina to ratify the young country’s new constitution were related to Elizabeth by blood, marriage or both. In the influential extended Barnwell family, Elizabeth’s brothers, John and especially Robert, became leading political figures in Beaufort.

Their prominence was reflected in the homes they built. Robert purchased and rebuilt Laurel Bay, his sister Anne Bull’s plantation home that had been burned by the British. Robert and Edward built an immense, three-story duplex on Bay Street known as “The Castle” for their sister-brides where they would raise their families side by side. In this heady climate, Elizabeth began construction on a magnificent tabby home for herself and her daughter.

In 1791, Marianna Gough married 30-year old James Harvey Smith of Charleston. From an equally well-connected family, he was a descendent of Governor James Moore and Colonel William Rhett, one of the most powerful of early Charles Town merchants. His siblings had married into the prominent Rutledge, Grimke and Bee families. Smith had studied in London and was regarded as having a fine intellect. Unfortunately his brilliance did not extend itself to the running of a plantation. About 1800, after an unsuccessful start as a planter in the Beaufort area, he and Marianna moved to a Cape Fear River plantation in North Carolina where his family had interests. In North Carolina, however, Smith enjoyed only modest success and all of the couple’s sons are believed to have been reared by their grandmother, Elizabeth, presumably for the benefits she could offer, not the least of which was the superior education available in Beaufort.

With the support of its wealthy planter population, Beaufort had earned a reputation for providing one of the finest educational opportunities in the South, most notably at Beaufort College. Originally located at Bay and Church Streets, it had among its original trustees the boys’ uncles, Robert and John, and a distinguished faculty that included the influential William J. Grayson and respected legal authority James Louis Petigru. Young men educated at Beaufort College frequently went on to distinguished academic careers at the country’s most respected universities.

When Elizabeth’s grandsons were still boys, they are said to have played frequently on the land facing the house. The land that had been an open field when the house was built was, by the time the boys played there, a town block. Between 1801 and 1809 Washington Street (along with Greene and Congress Streets) had been established by statute to accommodate a prospering Beaufort.

Elizabeth was reportedly a strict disciplinarian. Judging from the adult characters of her grandsons, she also instilled a good measure of her own personality and the Barnwell spirit before her death in 1817. Her influence may have even played a role in subsequent South Carolina history in the person of her fourth grandson, Robert Barnwell Rhett, the “Father of Secession.”

Elizabeth died in October of 1817 during one of the worst epidemics of yellow fever to hit Beaufort. By then her grandsons Thomas, James, Benjamin, Robert, Edmund and Albert were 23, 20, 19, 17, 9 and 7 years of age respectively. It has been a matter of speculation whether Elizabeth also had charge of her granddaughters. One fact perhaps supports the theory that the girls were reared by their parents in North Carolina. At the time of Elizabeth’s death and the Smiths’ subsequent return to Beaufort, their daughters Mariana, Claudia, Emma and Elizabeth were aged 18, 15, 14 and 2 respectively. Their eldest Mariana eventually married a North Carolinian, Dr. Joseph Rogers Walker. Making it plausible that the daughters were reared in North Carolina and only Mariana was old enough by 1817 to form an attachment there.

Whether Elizabeth reared only her grandsons or her granddaughters as well, the house was undoubtedly a hub of activity. The grandchildren had no fewer than 49 cousins from Elizabeth’s branch of the Barnwell family alone, all of whom most likely frequented the house, judging from the family’s numerous alliances with other Barnwell family members. Grandson Thomas married Caroline Barnwell (a daughter of Elizabeth’s brother Edward). Granddaughter Elizabeth married Nathaniel Barnwell Heyward (a son of another daughter of Edward’s). Edmund and Claudia married Stuarts. Robert Barnwell Rhett’s law partner was cousin Robert Woodward Barnwell, son of Elizabeth’s brother Robert.

Though Elizabeth was an anomaly for her era, a woman living independent of her husband, she was not living on the periphery of society. The countless connections and interconnections within the family and the Barnwell’s political and economic position in Beaufort would have made the house in Elizabeth’s lifetime part of the social fabric of Beaufort.

After Elizabeth’s death, James and Marianna Smith sold the house. And, with the sale and inheritance from Elizabeth’s estate, they presumably enjoyed a change in financial circumstances. For, while their elder sons benefited from an exceptionally fine education in Beaufort, many of their more affluent cousins were able to continue their education at New England preparatory schools and Ivy League colleges, an expense the couple could not afford for Thomas, James, Benjamin or Robert. But the two youngest Edmund and Albert went on to Philips Andover Academy after Elizabeth’s death with both grandsons eventually graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Yale.

James Smith died in 1835 and Marianna in 1837. She was buried in St. Helena’s Churchyard in the same plot as her mother. The weathered inscription on their marker reads simply:

BeneathThis Slab

Beside each other

Lie the remains of

Mrs. Elizabeth Gough

And her only child, and daughter

Mrs. Marianna Smith

The former dau of

Nathaniel and Mary Barnwell

and the wife of

Richard Gough

Was born on the 19th of June AD 1753

Died on the 10th day of Oct. AD 1817

The later wife of

James Smith

Was born on the 1 day of March 1773

And Died on 20 day of Oct. 1837

1De Sausaure’s Equity Reports, Vol. 2, page 197

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

.jpg)