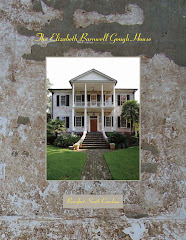

If you followed my suggestion to use the links at the right of this blog (under June) to read the history of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House in chronological order, you have now covered the first 80 years of its amazing history.

The presentation volume I prepared for the owners of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House covers the home's more than 220 year history, but with the first 80 years shown here, I believe, you have gained a good overview of the work I do.

For more information about Holme Histories and the research, writing and design services I offer, please go to holmehistories.com.

If you would like to contact me about preparing a presentation volume on your historic home, you may contact me through my writing and design company, Studio 602 at studio602@charter.net or through my website.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Penelope W. Holme

Thursday, June 11, 2009

Medicine in the Civil War

Medical practices in the mid-19th c. were still relatively primitive. With no understanding of the causes of infection or disease, hospitals were as deadly as the battlefield. Surgeons routinely operated with unwashed hands, garments soiled from previous patients and tools that had been given only a cursory cleaning by rinsing in the same bucket of water throughout the day. When available, ether, chloroform or whiskey were used as anesthetics. Frequently, though, even whiskey was unavailable and the patient had to endure the unabated pain of surgery.

Diarrhea or dysentery, the disease that killed the greatest numbers in the war, was treated typically with opium, copper sulfate, lead acetate, aromatic sulfuric acid, oil of turpentine, Epsom salts, castor oil, ipecac, sulfate of magnesia or mercurious chloride called calomel. Some were outright poisons. Others where administered with disastrous effects. A chronic lack of the medical supplies may have actually helped the survival rate at Hospital #10.

Amputations were routine. Often, piles of amputated limbs accumulated as overworked surgeons struggled to save the lives of soldiers shattered by two introductions in Civil War weaponry. The .58 caliber minié ball and canon loaded with canister shot both contributed to the war’s horrific numbers of dead and shattered or severed limbs.Statistics show that of those who had a shattered limb amputated, one in four would later die, most likely from infection – what was then called “surgical fever” – the primary killer of amputees.

So common was infection and so limited was medical knowledge that doctors at the time considered the symptoms of infection a natural, healthy sign of healing, even calling the symptoms “laudable pus.”

Gangrene was as little understood as dysentery. Stumps of amputees were routinely treated with such caustic chemicals or irritants as nitric acid and turpentine.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Battle of Battery Wagner

In mid-July of 1863, Union forces under the command of General Quincy Gillmore began a siege to retake Fort Sumter and capture Charleston. In the ring of Confederate defenses was Battery Wagner on Morris Island, a man-made mountain of sand, palmetto logs and cannon.

Gillmore’s intention was first to reduce the battery with prolonged shelling and then overtake it with ground forces. The battery’s sand construction, however, made it ideally suited to absorb the impact of the 9,000 shells fired into the fort in one day. When the Union finally launched its troops, with the Massachusetts 54th spearheading the attack, the battery’s strength was virtually undiminished.

In command of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment was Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the 27 year old son of one of Boston’s most prominent and ardent abolitionist families. Shaw and his men in a heroic charge stormed the battery and might have succeeded in overtaking it had reinforcements arrived in time.

Shaw was killed as were 44 of his men. Another 49 were listed as missing presumed dead and 29 were captured. Wounded totaled 150 from the initial attack and withdrawal.

In what would become a 58-day siege the Union would incur 1,515 killed, wounded or captured. The Massachusetts 54th lost nearly half its force of 600. The carnage at Battery Wagner was only a fraction of the 12,000 men the Union lost at Antietam or the more than 10,000 lost at Fredericksburg. The significance of the battle was, however, not due to its size.

With Charleston considered the breeding ground of secessionist sentiment (or cradle depending on one’s allegiance) and Fort Sumter the birthplace of the war, the symbolic value of the two was as great or perhaps even greater than their military value on both sides. By eventually prevailing at Battery Wagner, the North had achieved an important moral victory.

An equally important moral victory on Morris Island was won by the Massachusetts 54th. Although they had acquitted themselves bravely under fire prior the Battle of Battery Wagner, the high profile siege on Morris Island had earned them what they sought most – resounding proof of their quality as soldiers and as men. Their bravery had earned the respect of the white troops on Morris Island, a glowing report of their bravery in The New York Herald and praise from President Abraham Lincoln.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Fighting for Equality - The Colored Regiments

On November 7, 1862, exactly one year after the Day of the Big Gun Shoot, The 1st South Carolina Volunteers became the first colored regiment to be mustered into Union forces. Formed almost entirely of former slaves, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers were known as a “contraband” regiment.

Early in 1863, the regiment was joined in Beaufort by the first regiment of free blacks, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers.

In its ranks were blacks who had escaped to the North and freedom and many others who had never known slavery. Serving in the Massachusetts 54th were graduates of Oberlin College, two of Frederick Douglass’ sons, successful business men and former teachers.

Eventually joining them in the war were more than 160 colored regiments, including Beaufort’s second contraband regiment the 2nd SC Volunteers.A total of more than 180,000 black soldiers fought on the side of the Union – though the vast majority enlisted without the encouragement of Frederick Douglass’s words...

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”...they shared the goal.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Susie King Taylor

Born into slavery on Isle of Wight, one of Georgia’s Sea Islands, then Susie King was raised primarily by her grandmother in Savannah. Attending a clandestine school for blacks, she learned to read and write as a child. At fourteen, using the confusion created by the assault on Fort Pulaski, she escaped with an uncle to Union forces and freedom.

She found employment with the 1st SC Volunteers as a laundress and an unofficial teacher. At the age of fourteen, she married Edward King, one of the regiment’s soldiers. She later served at Hospital #10 as an unofficial nurse following the regiment’s campaigns in Florida and the assault on Battery Wagner.

Following the Civil War, she became a widow at only 18. She supported herself teaching school for several years before writing her autobiography, one of the few accounts of slave life and the Civil War from a black perspective.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Clara Barton

.jpg)

When the Civil War began, Clara Barton was working as a copyist in the US Patent Office in Washington. Already a social pioneer, she was one of only four women employed by the US government at the time and the only one not filling in for a husband serving in the Union army.

Shocked by the horrific lack of care for wounded following the Battle of Bull Run, she was determined to deliver better and more immediate care to soldiers. Soliciting needed medical supplies, foods and clothing on her own, she also defied the restrictive social conventions for women and personally brought nursing care for the first time to wounded in the field.

Often dangerously close to battle lines and remarkably heedless of her own safety, Barton tended the wounded following the Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam and Fredricksburg. In-field nursing would not be provided by the Sanitation Commission (the official source of nursing care during the war) until five months later. Jealous of its official status, the Commission frowned on Barton as an independent agent and sought to bar her from their hospitals.

The search for a venue where she could serve brought Barton to South Carolina and ultimately to Morris Island where she helped with the wounded following the assault on Battery Wagner.

Although the hospitals in Beaufort were under the auspices of the Sanitary Commission, Barton managed an unofficial visit to Hospital #10. She was acquainted with Col. Higginson commander of the 1st SC Volunteers and the visit may have been at his urging or at the invitation of Regiment Surgeon Dr. Ruggers. Conducting her unofficial tour was another remarkable woman at Hospital #10, Susie King Taylor. Impressed by Barton’s attention and kindness to the black wounded, Susie King Taylor would later write “I honored her for her devotion and care for those men.”20

Later, with government backing, Barton would bring to public attention the atrocities at Andersonville Prison. Still later, she served with the German Red Cross in the Franco-Prussian War, as a nurse during the Spanish American War and is credited with the founding of the American Red Cross.

20 Susie King Taylor, A Black Woman’s Civil War Memoirs, Markus Wiener Publishing, New York, Seventh Printing, 1999, page 67

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Harriet Tubman

In 1849, Harriet Tubman fled the Eastern Shore of Maryland to make her way north to freedom. It was to become the first trip of many, as she returned repeatedly to lead others north. Her multiple trips conducting family and fellow slaves along the Underground Railroad eventually earned her the epithet of Moses and the friendship of many prominent abolitionists, including Frederick Douglas, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Franklin B. Sanborn and John Brown. It also brought her to the attention of Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts.

In January 1862, Governor Andrew – recognizing Tubman’s ability to slip in and out of Confederate territory undetected – made arrangements for her to travel to South Carolina to serve as a spy. Although small in stature, illiterate and handicapped by epileptic- like seizures (caused by a head injury she sustained while a slave), Harriet Tubman proved to be an important asset to the Union. On June 2nd of that year, she became the first woman to plan and lead a military raid behind Confederate lines. With 300 soldiers of Col. James Montgomery’s 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, she executed a brilliant and successful raid that destroyed millions of dollars worth of valuable Confederate stores and spirited away 800 slaves without a single injury to the 2nd SC Volunteers.

In July 1863, Tubman like many of the women in Beaufort and the Sea Islands, was called to nursing duty following the assault on Battery Wagner. From her we have one of the most descriptive accounts of the horrific conditions in the hospitals following the battle.

“I’d go to the hospital, I would, early every morning. I’d get a big chunk of ice, I would, and put it in a basin, and fill it with water; then I’d take a sponge and begin. First man I’d come to, I’d thrash away the flies, and they’d rise, they would, like bees round a hive. Then I’d begin to bathe their wounds, and by the time I’d bathed off three or four, the fire and heat would have melted the ice and made the water warm, and it would be as red as clear blood. Then I’d go and get more ice, I would, and by the time I got to the next ones, the flies would be round de first ones, black and thick as ever.” 19

Although no written record has as yet been found indicating at which hospital(s) Harriet Tubman served, what we do know points strongly to her presence at Hospital #10.

Many of the women who had been pressed into nursing service at the hospitals fell ill from the around the clock work in Beaufort’s heat and humidity and from the same diseases that took their toll among the soldiers. Among those affected at one point was Esther Hill Hawks.

We know that Tubman (apparently immune to the heat, exhaustion and diseases that felled other nurses) frequently stepped into posts vacated by ill nurses. Making speculation that Tubman may have served at Hospital #10 (either along side Hawks or during her absence) even more probable is an entry in the diary of Charlotte Forten.

A young, educated black woman from Philadelphia, Forten had come to Beaufort to aid in the Port Royal Experiment as a teacher. An entry from January 31, 1863 recounts the attempt she and Harriet Tubman made to call on Esther Hill Hawks, only to find that she was not in town at the time but at Fort Saxton with her husband. The wording of the entry suggests that it was not an attempt at an introduction but a simple social call, indicating that Hawks and Tubman were indeed acquainted.

Also pointing to her probable presence at Hospital #10 is Tubman’s connection with the Massachusetts 54th. Tubman was close friends with Frederick Douglass, who had campaigned for the forming of the regiment and had contributed two of his sons to its ranks. The regiment was also authorized by Governor Andrew, a sponsor of Tubman’s.

Tubman, like Douglass, was from the Eastern Shore of Maryland as were all of the slaves she had led to freedom. The black community, both free and slave, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland was uniquely mobile and interconnected. Slaves were frequently hired out to plantations often at some distance. Both free and enslaved blacks regularly worked side by side. The practice created broad circles of acquaintanceship, friendship and family in the Eastern Shore black community.

Many of the slaves Tubman led to freedom eventually settled in central New York state near where Harriet Tubman’s own family had settled in in the town of Auburn and where Harriet Tubman was a prominent figure in the black community. Frederick Douglass also actively conducted recruiting for the Massachusetts 54th in the area. It is reasonable to assume that Tubman would have had personal connections with many of the soldiers in the Massachusetts 54th, such as Charley Reason mentioned in Esther Hill Hawks’ diary. He had been a slave in Maryland before escaping and settling in Syracuse. Almost certainly Tubman would have known him as well as many of his fellow soldiers.

Although the large number of wounded from the Massachusetts 54th necessitated that multiple buildings around Beaufort be used as hospitals, given Tubman’s energy and devotion, it is hard to imagine that she never called on the wounded in Hospital #10.

Also adding to her probable presence at Hospital #10 is her close connection with the 2nd SC Volunteers whose wounded were also sent to Hospital #10. Tubman served with the 2nd SC Volunteers through the spring of 1864, earning praise from General Rufus Saxton, Col. Thomas Higginson and all who witnessed her courage and devotion.

After the war, she remained active in the black community and like many of the women in the abolitionist movement, she became a voice for women’s suffrage.

19Sarah H. Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, WJ Moses, Auburn, NY, 1869, as cited by Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land, Harriet Tubman Portrait of an American Hero, Ballantine Books, New York, NY, 2004, page 221

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)