On November 7, 1861 the Civil War arrived in Beaufort with one, cataclysmic battle. In only a few hours, what had been the home of one of the most ardent champions of secession and slavery, fell to the Union. Still other forces, however, were about to overtake Beaufort with even more profound effect, for Beaufort was about to become the stage for “the most drastic social changes ever attempted in American History.”14

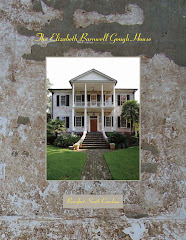

Nowhere were these changes more poignantly reflected than in the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House. One of Beaufort’s grandest homes, it stood before the war as a symbol of the town’s wealth and privilege. As the boyhood home of the Father of Secession, it was also a symbol of Beaufort as the cradle of Secessionist sentiment. With no little irony, two years to the day after the firing on Fort Sumter, it would become a hospital serving the wounded from three of the most celebrated black regiments fighting for the Union and equality.

The Massachusetts 54th, the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteers – together with the Northern abolitionists and doctors John Milton Hawks and wife Esther Hill Hawks, Clara Barton, Susie King Taylor and in all likelihood famed Harriet Tubman – came to 705 Washington Street as they played their parts in one of the most important dramas of the age.For, immediately upon occupying Beaufort, the Union appropriated many of the abandoned homes. A few served as headquarters for high ranking officers or administrative officials, others for billeting subordinates and a number as hospitals.

Initially, hospitals in Beaufort served both white and black wounded, but the arrangement proved unsatisfactory. Though the black soldiers were showing themselves to be more than competent on the battlefield, their Northern counterparts often resented their presence in the hospitals and vented their prejudice with verbal abuse and petty acts of harassment. Worse was the fact that the black soldiers often received unequal medical care. On the 12th of April 1863, the War Department responded to the need for separate facilities for white and black soldiers by making the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House the first sanctioned hospital for colored soldiers, known as Hospital #10.*

The first wounded to come to the hospital were from the 1st South Carolina Volunteers after the Jacksonville expedition. The first of a series of forays conducted from Beaufort into Confederate Florida, the expedition was also the first to prove the 1st SC Volunteers in battle. The soldiers performed so well both in training and under fire that their commander, Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, wrote in his journal that the question had become not whether black soldiers would be as good as whites, but if the black soldiers were in actuality better.

In charge of the hospital was Dr. John Milton Hawks, an ardent abolitionist from New Hampshire. His wife Esther Hill Hawks served as a nurse and her brother as steward. It is from her diaries that we have accounts of the early months of the house’s tenure as Hospital #10, starting with its earliest days.“The house was one of the Barnwell mansions – and when our troops came here, magnificently furnished but 18 months occupation by soldiers leaves nothing but a filthy shell; Mrs. Strong, wife of our Maj. was appointed nurse by Mrs. Lander**, and she and I went about for weeks with rag in hand, overseeing and instructing in cleaning. We already had between 20 and 30 patients – and this, with getting things in order, kept us very busy.”15

The 20 or 30 initial patients were soon overtaken by a much larger number of wounded from the famed Battle of Battery Wagner.

Again from Esther Hill Hawks’ diary –“July18th! never to be forgotten day! After many days of anxious waiting the news came, “Prepare immediately to receive 500 wounded men,” indeed they were already at the dock! And before morning we had taken possession of the building where our first hospital was started… 150 of the brave boys from the 54th Mass. Col. Shaw’s Regt. Were brought to us and laid on blankets on the floor all mangled and ghastly. What a terrible sight it was! It was 36 hours since the awful struggle…and nothing had been done for them. We had no beds, and no means of building a fire, but the colored people came promptly to our aid and almost before we knew what we needed they brought us buckets full of nice broth and gruels, pitchers of lemonade, fruits cakes, vegetables indeed everything needed for the immediate wants of the men was furnished – not for one day but for many (Then too the Sanitary Com. Blessed us with its ready aid. Everything for our immediate wants was furnished and in 24 hours the poor fellows were lying with clean clothes and dressed wounds in comfortable beds, and we breathed freely again) before setting about creating a hospital: no one, unless they have had the experience can imagine the amount of work and worry needed in setting one of these vast military machines in motion! And in this case humanity demanded that the poor fellows who had fought so bravely, should be first attended to. The colored people still continued to supply delicacies and more substantial aid came from the citizens and Sanitary Com. (It was a busy time, and the amount of work done in the first 24 hours, by the two surgeons, and one sick woman is tiresome to remember! The only thing that sustained us was the patient endurance of those stricken heroes before us, with their ghastly wounds cheerful & courageous, many a poor fellow sighing that his right arm was shattered beyond hope of striking another blow for freedom!…”16

The August 1, 1863 issue of the Beaufort newspaper The Free South lists the names of 67 members of the 54th in Hospital #10.Elias Artist, G. Alexander, John Barker, Samuel Berry, John A. Boulden, W. Briggs, David Bronson, Thomas E. Burley, Thos. E. Buyers, Wm. Buyers, C. Charlton, Callhill Charlton, Jacob Christy, Charles Clark, James Cole, James Coleman, James Conkleton, Wesley Conkleton, Wm. Conkleton, Thomas Cooper, Anthony Dean, Samuel DeForrest, L. Delaney, G. Fisher, Eli Franklin, Joseph Gallas, Martin Gilman, Peter Glasby, P. Glastnally, Charles Goff, Benj. Granger, G.H. Hall, G. Harlbart, John Hedgepath, A. Hill, James Jackson, Sanford Jackson, John Johnson, Joseph Johnson, B. Krass, John L. King, W.R. Lee, John Lott, V.M. Mago, Edw. Mills, Wm. Milton, John Mogan, Samuel Moles, J.H. Montgomery, J.A. Palmer, Ned Pegrin, John Price, W.A. Rankins, Charles K. Reason, James Riley, George Rivers, G. Rust, John Shafter, B. Smith, Jr., B. Thompson, G. Thompson, Sam Tipton, H. Tucker, John Turner, George Washington, H. White, Chas. Whitney, Edward Williams, S. Winnis

From Esther Hill Hawks’ diary we get to know some of the men behind the names.“Many have died, several cases of gangrene have been provided for in tents: Two severe amputations today neither surviving but a few hours. One of these, a boy hardly 20 years old, Charley Reason, formerly a slave, but of late years resident in Syracuse NY., I have taken a great interest in; he is such a noble looking fellow, and so uncomplaining – so grateful when I bathe his head and face, as I sat by him holding his one poor hand! Oh yes! He said in reply to my question of why he came to war! I know what I am fighting for, only a few years ago I ran away from a man in Maryland who said he owned me and since then I’ve worked on a farm in Syracuse but as soon as the government would take me I came to fight, not for my country, I never had any, but to gain one[.]

“I find many of these men have been slaves, but by far the greater proportion were born and bred in the free north -- A few are from Canada. Some few well educated -- three graduates from Oberlin. They are intelligent, courteous, cheerful and kind, and I pity the humanity which, on close acquaintance with these men, still retains the unworthy prejudice against color!

"Three Krunkleton [sic] brothers, noble, stalwart men, lay side by side severely wounded! The fourth who had left home with them fell and was buried with his Col. at Fort Wagna [Battery Wagner...]

"One young man, Jonny Lott, one of my especial pets a handsome boy, a mere boy, who had come from the far west to bear his part of suffering, had his right arm shattered and his life was, for many days, despaired of, and in the long days of weary restlessness I learned the brave spirit of the boy well. He was well educated – had taught a term in a colored school[...]

"[T]he seventy under our care won golden opinions from us all by their patience in bearing the petty annoyances and deprivations to which all must be subjected – and during the two months that I went in and out among them no difficulties occurred which my presence and word could not settle. I endeavored with my whole heart, to make this dreary hospital life, as home-like as possible — and I was richly rewarded by their grateful thanks.”17

The hospital’s tenure as a place of compassionate care changed, however, by mid-September of that year when Dr. Charles Mead, formerly the Assistant Surgeon of the 112th New York Infantry was placed in charge. Esther Hill Hawks left the hospital at about the same time, returning in October and November as a teacher. She describes Dr. Mead as “a young, ineficient disipated negro-hating tyrant.” Embezzler of foods and clothing sent to the 54th Massachusetts from Boston, Dr. Mead was “most heartily hated by the men”…and “soon ran his course in the hospital, but not before almost every patient in it had served a few days in the jail for some trivial offense.”18

In November, Esther Hill Hawks left the hospital to join her husband, John Milton Hawks, recently promoted to Surgeon for the 3rd SC Regiment on Hilton Head Island. With her departure, her first hand account of life in Hospital #10 ends.

The Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House, though, continued to serve as Hospital #10 as Beaufort’s black troops continued to see battle. In January of 1864, the troops played a major role in the Battle of Olustee, Florida. Five months before the war’s end they served at the Battle of Honey Hill and on April 18, 1865, nine days after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, the Massachusetts 54th fought in the Battle of Boykins Mill. It was the last battle of the war in South Carolina thus bringing their service and the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House’s tenure as a hospital to an end.

*Later in the war two neighboring buildings – the H. M. Fuller House (where the University of South Carolina Performing Arts Building now stands) and the Beaufort College Building (in the Civil War era photo at left)– were also converted to hospitals and were known collectively with the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House as the Hospital #10 complex.

**A former actress and head of the Sanitary Commision in Beaufort

14. Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, the Port Royal Experiment, University of Georgia Press, Athens Georgia, 1964, page xi

15 The Diary of Esther Hill Hawks as cited by Gerald Swartz, A Woman Doctor’s Civil War, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC 1984, page 48

16Ibid,, page 50

17Ibid, page 51

18Ibid, page 54

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

.jpg)