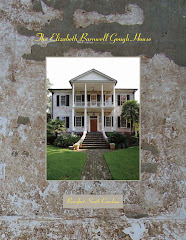

If you followed my suggestion to use the links at the right of this blog (under June) to read the history of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House in chronological order, you have now covered the first 80 years of its amazing history.

The presentation volume I prepared for the owners of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House covers the home's more than 220 year history, but with the first 80 years shown here, I believe, you have gained a good overview of the work I do.

For more information about Holme Histories and the research, writing and design services I offer, please go to holmehistories.com.

If you would like to contact me about preparing a presentation volume on your historic home, you may contact me through my writing and design company, Studio 602 at studio602@charter.net or through my website.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Penelope W. Holme

Thursday, June 11, 2009

Medicine in the Civil War

Medical practices in the mid-19th c. were still relatively primitive. With no understanding of the causes of infection or disease, hospitals were as deadly as the battlefield. Surgeons routinely operated with unwashed hands, garments soiled from previous patients and tools that had been given only a cursory cleaning by rinsing in the same bucket of water throughout the day. When available, ether, chloroform or whiskey were used as anesthetics. Frequently, though, even whiskey was unavailable and the patient had to endure the unabated pain of surgery.

Diarrhea or dysentery, the disease that killed the greatest numbers in the war, was treated typically with opium, copper sulfate, lead acetate, aromatic sulfuric acid, oil of turpentine, Epsom salts, castor oil, ipecac, sulfate of magnesia or mercurious chloride called calomel. Some were outright poisons. Others where administered with disastrous effects. A chronic lack of the medical supplies may have actually helped the survival rate at Hospital #10.

Amputations were routine. Often, piles of amputated limbs accumulated as overworked surgeons struggled to save the lives of soldiers shattered by two introductions in Civil War weaponry. The .58 caliber minié ball and canon loaded with canister shot both contributed to the war’s horrific numbers of dead and shattered or severed limbs.Statistics show that of those who had a shattered limb amputated, one in four would later die, most likely from infection – what was then called “surgical fever” – the primary killer of amputees.

So common was infection and so limited was medical knowledge that doctors at the time considered the symptoms of infection a natural, healthy sign of healing, even calling the symptoms “laudable pus.”

Gangrene was as little understood as dysentery. Stumps of amputees were routinely treated with such caustic chemicals or irritants as nitric acid and turpentine.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Battle of Battery Wagner

In mid-July of 1863, Union forces under the command of General Quincy Gillmore began a siege to retake Fort Sumter and capture Charleston. In the ring of Confederate defenses was Battery Wagner on Morris Island, a man-made mountain of sand, palmetto logs and cannon.

Gillmore’s intention was first to reduce the battery with prolonged shelling and then overtake it with ground forces. The battery’s sand construction, however, made it ideally suited to absorb the impact of the 9,000 shells fired into the fort in one day. When the Union finally launched its troops, with the Massachusetts 54th spearheading the attack, the battery’s strength was virtually undiminished.

In command of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment was Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the 27 year old son of one of Boston’s most prominent and ardent abolitionist families. Shaw and his men in a heroic charge stormed the battery and might have succeeded in overtaking it had reinforcements arrived in time.

Shaw was killed as were 44 of his men. Another 49 were listed as missing presumed dead and 29 were captured. Wounded totaled 150 from the initial attack and withdrawal.

In what would become a 58-day siege the Union would incur 1,515 killed, wounded or captured. The Massachusetts 54th lost nearly half its force of 600. The carnage at Battery Wagner was only a fraction of the 12,000 men the Union lost at Antietam or the more than 10,000 lost at Fredericksburg. The significance of the battle was, however, not due to its size.

With Charleston considered the breeding ground of secessionist sentiment (or cradle depending on one’s allegiance) and Fort Sumter the birthplace of the war, the symbolic value of the two was as great or perhaps even greater than their military value on both sides. By eventually prevailing at Battery Wagner, the North had achieved an important moral victory.

An equally important moral victory on Morris Island was won by the Massachusetts 54th. Although they had acquitted themselves bravely under fire prior the Battle of Battery Wagner, the high profile siege on Morris Island had earned them what they sought most – resounding proof of their quality as soldiers and as men. Their bravery had earned the respect of the white troops on Morris Island, a glowing report of their bravery in The New York Herald and praise from President Abraham Lincoln.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Fighting for Equality - The Colored Regiments

On November 7, 1862, exactly one year after the Day of the Big Gun Shoot, The 1st South Carolina Volunteers became the first colored regiment to be mustered into Union forces. Formed almost entirely of former slaves, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers were known as a “contraband” regiment.

Early in 1863, the regiment was joined in Beaufort by the first regiment of free blacks, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers.

In its ranks were blacks who had escaped to the North and freedom and many others who had never known slavery. Serving in the Massachusetts 54th were graduates of Oberlin College, two of Frederick Douglass’ sons, successful business men and former teachers.

Eventually joining them in the war were more than 160 colored regiments, including Beaufort’s second contraband regiment the 2nd SC Volunteers.A total of more than 180,000 black soldiers fought on the side of the Union – though the vast majority enlisted without the encouragement of Frederick Douglass’s words...

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”...they shared the goal.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Susie King Taylor

Born into slavery on Isle of Wight, one of Georgia’s Sea Islands, then Susie King was raised primarily by her grandmother in Savannah. Attending a clandestine school for blacks, she learned to read and write as a child. At fourteen, using the confusion created by the assault on Fort Pulaski, she escaped with an uncle to Union forces and freedom.

She found employment with the 1st SC Volunteers as a laundress and an unofficial teacher. At the age of fourteen, she married Edward King, one of the regiment’s soldiers. She later served at Hospital #10 as an unofficial nurse following the regiment’s campaigns in Florida and the assault on Battery Wagner.

Following the Civil War, she became a widow at only 18. She supported herself teaching school for several years before writing her autobiography, one of the few accounts of slave life and the Civil War from a black perspective.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Clara Barton

.jpg)

When the Civil War began, Clara Barton was working as a copyist in the US Patent Office in Washington. Already a social pioneer, she was one of only four women employed by the US government at the time and the only one not filling in for a husband serving in the Union army.

Shocked by the horrific lack of care for wounded following the Battle of Bull Run, she was determined to deliver better and more immediate care to soldiers. Soliciting needed medical supplies, foods and clothing on her own, she also defied the restrictive social conventions for women and personally brought nursing care for the first time to wounded in the field.

Often dangerously close to battle lines and remarkably heedless of her own safety, Barton tended the wounded following the Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam and Fredricksburg. In-field nursing would not be provided by the Sanitation Commission (the official source of nursing care during the war) until five months later. Jealous of its official status, the Commission frowned on Barton as an independent agent and sought to bar her from their hospitals.

The search for a venue where she could serve brought Barton to South Carolina and ultimately to Morris Island where she helped with the wounded following the assault on Battery Wagner.

Although the hospitals in Beaufort were under the auspices of the Sanitary Commission, Barton managed an unofficial visit to Hospital #10. She was acquainted with Col. Higginson commander of the 1st SC Volunteers and the visit may have been at his urging or at the invitation of Regiment Surgeon Dr. Ruggers. Conducting her unofficial tour was another remarkable woman at Hospital #10, Susie King Taylor. Impressed by Barton’s attention and kindness to the black wounded, Susie King Taylor would later write “I honored her for her devotion and care for those men.”20

Later, with government backing, Barton would bring to public attention the atrocities at Andersonville Prison. Still later, she served with the German Red Cross in the Franco-Prussian War, as a nurse during the Spanish American War and is credited with the founding of the American Red Cross.

20 Susie King Taylor, A Black Woman’s Civil War Memoirs, Markus Wiener Publishing, New York, Seventh Printing, 1999, page 67

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Harriet Tubman

In 1849, Harriet Tubman fled the Eastern Shore of Maryland to make her way north to freedom. It was to become the first trip of many, as she returned repeatedly to lead others north. Her multiple trips conducting family and fellow slaves along the Underground Railroad eventually earned her the epithet of Moses and the friendship of many prominent abolitionists, including Frederick Douglas, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Franklin B. Sanborn and John Brown. It also brought her to the attention of Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts.

In January 1862, Governor Andrew – recognizing Tubman’s ability to slip in and out of Confederate territory undetected – made arrangements for her to travel to South Carolina to serve as a spy. Although small in stature, illiterate and handicapped by epileptic- like seizures (caused by a head injury she sustained while a slave), Harriet Tubman proved to be an important asset to the Union. On June 2nd of that year, she became the first woman to plan and lead a military raid behind Confederate lines. With 300 soldiers of Col. James Montgomery’s 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, she executed a brilliant and successful raid that destroyed millions of dollars worth of valuable Confederate stores and spirited away 800 slaves without a single injury to the 2nd SC Volunteers.

In July 1863, Tubman like many of the women in Beaufort and the Sea Islands, was called to nursing duty following the assault on Battery Wagner. From her we have one of the most descriptive accounts of the horrific conditions in the hospitals following the battle.

“I’d go to the hospital, I would, early every morning. I’d get a big chunk of ice, I would, and put it in a basin, and fill it with water; then I’d take a sponge and begin. First man I’d come to, I’d thrash away the flies, and they’d rise, they would, like bees round a hive. Then I’d begin to bathe their wounds, and by the time I’d bathed off three or four, the fire and heat would have melted the ice and made the water warm, and it would be as red as clear blood. Then I’d go and get more ice, I would, and by the time I got to the next ones, the flies would be round de first ones, black and thick as ever.” 19

Although no written record has as yet been found indicating at which hospital(s) Harriet Tubman served, what we do know points strongly to her presence at Hospital #10.

Many of the women who had been pressed into nursing service at the hospitals fell ill from the around the clock work in Beaufort’s heat and humidity and from the same diseases that took their toll among the soldiers. Among those affected at one point was Esther Hill Hawks.

We know that Tubman (apparently immune to the heat, exhaustion and diseases that felled other nurses) frequently stepped into posts vacated by ill nurses. Making speculation that Tubman may have served at Hospital #10 (either along side Hawks or during her absence) even more probable is an entry in the diary of Charlotte Forten.

A young, educated black woman from Philadelphia, Forten had come to Beaufort to aid in the Port Royal Experiment as a teacher. An entry from January 31, 1863 recounts the attempt she and Harriet Tubman made to call on Esther Hill Hawks, only to find that she was not in town at the time but at Fort Saxton with her husband. The wording of the entry suggests that it was not an attempt at an introduction but a simple social call, indicating that Hawks and Tubman were indeed acquainted.

Also pointing to her probable presence at Hospital #10 is Tubman’s connection with the Massachusetts 54th. Tubman was close friends with Frederick Douglass, who had campaigned for the forming of the regiment and had contributed two of his sons to its ranks. The regiment was also authorized by Governor Andrew, a sponsor of Tubman’s.

Tubman, like Douglass, was from the Eastern Shore of Maryland as were all of the slaves she had led to freedom. The black community, both free and slave, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland was uniquely mobile and interconnected. Slaves were frequently hired out to plantations often at some distance. Both free and enslaved blacks regularly worked side by side. The practice created broad circles of acquaintanceship, friendship and family in the Eastern Shore black community.

Many of the slaves Tubman led to freedom eventually settled in central New York state near where Harriet Tubman’s own family had settled in in the town of Auburn and where Harriet Tubman was a prominent figure in the black community. Frederick Douglass also actively conducted recruiting for the Massachusetts 54th in the area. It is reasonable to assume that Tubman would have had personal connections with many of the soldiers in the Massachusetts 54th, such as Charley Reason mentioned in Esther Hill Hawks’ diary. He had been a slave in Maryland before escaping and settling in Syracuse. Almost certainly Tubman would have known him as well as many of his fellow soldiers.

Although the large number of wounded from the Massachusetts 54th necessitated that multiple buildings around Beaufort be used as hospitals, given Tubman’s energy and devotion, it is hard to imagine that she never called on the wounded in Hospital #10.

Also adding to her probable presence at Hospital #10 is her close connection with the 2nd SC Volunteers whose wounded were also sent to Hospital #10. Tubman served with the 2nd SC Volunteers through the spring of 1864, earning praise from General Rufus Saxton, Col. Thomas Higginson and all who witnessed her courage and devotion.

After the war, she remained active in the black community and like many of the women in the abolitionist movement, she became a voice for women’s suffrage.

19Sarah H. Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, WJ Moses, Auburn, NY, 1869, as cited by Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land, Harriet Tubman Portrait of an American Hero, Ballantine Books, New York, NY, 2004, page 221

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Esther Hill Hawks

While the Massachusetts 54th and the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteers fought for equality for America’s black population on the battlefield, Esther Hill Hawks was one of the missionaries who came from the North to fight for the same goal in the classroom.

One of the great ironies at Hospital #10 was that Esther Hill Hawks, one of the earliest women doctors in the US, was unable to serve officially as either a doctor or a nurse. She had earned her medical degree in 1857, shortly after her marriage to John Milton Hawks. A doctor himself, he was not as progressive in his thinking as Esther and lamented that he would have preferred her to tend to his comfort rather than her medical studies.

Esther overcame his objections but was unable to overcome the gender prejudice of the era. Unable to secure a position as a doctor, she attempted to find service with the army as a nurse. But Dorothea Dix, head of nursing for the Sanitary Commission, the organization appointed by the government to assist with sick and wounded soldiers, would not employ nurses who were young or attractive. And Esther had the misfortune of being both.

Given the desperate need for nurses during the war, it seems unfathom able in today’s light that Esther Hill Hawks would be rejected. Social conventions of the time, however, were rigid. Women of good reputation did not venture out unescorted and certainly not in the company of men. With the necessity of having nurses and soldiers in close proximity, Dix’s intention presumably was to avoid any hint of impropriety.

Eager to serve in the war effort and wanting to join her husband (who had received appointment as U.S. Army Acting Assistant Surgeon on the staff of General Rufus Saxton in Beaufort), she secured a position as a teacher of freedmen with the National Freedman’s Relief Assoc.

Her first duties as teacher were with the 1st SC Volunteers. So great was the desire of former slaves to learn to read that the army made teachers available as one of the benefits of enlistment. Her connection with the 1st SC Volunteers eventually led her to Hospital #10 where she served as teacher, nurse and ultimately an unofficial Surgeon, the title at the time for doctors. From the back porch of Hospital #10, Esther reviewed soldiers reporting in sick. When the lack of a male doctor at Hospital #10 was discovered, Esther was relieved of duty. But she at least had served for a brief period in her chosen profession, albeit unofficially.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Port Royal Experiment

Drawn to Beaufort were some of the most ardent abolitionists, forward thinkers and extraordinary figures of the era. The majority, though, had in actuality no or little direct experience with slavery and had little idea what to expect or how to proceed.

Great uncertainty revolved around the best method for aiding in the transition. Some believed the key was in education, for others it was economic and for still others it was military service. At times, those with even the best motives (and those with less altruistic objectives) would clash. Collectively, their efforts came to known as the Port Royal Experiment as the potential routes to a new society were tested.

So great was their vision and so large their hopes, it is easy to lose sight of how small the stage was for their efforts. Their grand view for the future of former slaves and the future of the South would be tried in tiny Beaufort and acted out in part on the smaller stage of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Union Occupation

On November 9th, the North occupied a town that had only 48 hours before belonged to one of the wealthiest, most privileged classes ever to exist in the US. Union diaries from the time describe with awe the still impressive homes and the lush gardens that now bore the scars of indiscriminant destruction and looting. Union forces under General Isaac Stevens put an end to looting both by former slaves and later by soldiers, but ironically was unable to prevent the more systematic sacking of valuable goods by Northern agents who had arrived on the heels of the military. The physical changes to Beaufort, though, were only a prelude to the social changes about to take place.

After the restoration of order, the Department of the South, as Beaufort was now known in Washington, had two pressing challenges to address: the waging of the war and what to do ultimately about the huge slave population that had been largely cast adrift. In response to the latter, abolitionist groups in the North rapidly organized to create Freedman Aid Societies, sending supplies, clothing and most significantly teachers to help the former slaves in the transition to freedom.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Monday, June 8, 2009

Union Hospital #10

On November 7, 1861 the Civil War arrived in Beaufort with one, cataclysmic battle. In only a few hours, what had been the home of one of the most ardent champions of secession and slavery, fell to the Union. Still other forces, however, were about to overtake Beaufort with even more profound effect, for Beaufort was about to become the stage for “the most drastic social changes ever attempted in American History.”14

Nowhere were these changes more poignantly reflected than in the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House. One of Beaufort’s grandest homes, it stood before the war as a symbol of the town’s wealth and privilege. As the boyhood home of the Father of Secession, it was also a symbol of Beaufort as the cradle of Secessionist sentiment. With no little irony, two years to the day after the firing on Fort Sumter, it would become a hospital serving the wounded from three of the most celebrated black regiments fighting for the Union and equality.

The Massachusetts 54th, the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteers – together with the Northern abolitionists and doctors John Milton Hawks and wife Esther Hill Hawks, Clara Barton, Susie King Taylor and in all likelihood famed Harriet Tubman – came to 705 Washington Street as they played their parts in one of the most important dramas of the age.For, immediately upon occupying Beaufort, the Union appropriated many of the abandoned homes. A few served as headquarters for high ranking officers or administrative officials, others for billeting subordinates and a number as hospitals.

Initially, hospitals in Beaufort served both white and black wounded, but the arrangement proved unsatisfactory. Though the black soldiers were showing themselves to be more than competent on the battlefield, their Northern counterparts often resented their presence in the hospitals and vented their prejudice with verbal abuse and petty acts of harassment. Worse was the fact that the black soldiers often received unequal medical care. On the 12th of April 1863, the War Department responded to the need for separate facilities for white and black soldiers by making the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House the first sanctioned hospital for colored soldiers, known as Hospital #10.*

The first wounded to come to the hospital were from the 1st South Carolina Volunteers after the Jacksonville expedition. The first of a series of forays conducted from Beaufort into Confederate Florida, the expedition was also the first to prove the 1st SC Volunteers in battle. The soldiers performed so well both in training and under fire that their commander, Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, wrote in his journal that the question had become not whether black soldiers would be as good as whites, but if the black soldiers were in actuality better.

In charge of the hospital was Dr. John Milton Hawks, an ardent abolitionist from New Hampshire. His wife Esther Hill Hawks served as a nurse and her brother as steward. It is from her diaries that we have accounts of the early months of the house’s tenure as Hospital #10, starting with its earliest days.“The house was one of the Barnwell mansions – and when our troops came here, magnificently furnished but 18 months occupation by soldiers leaves nothing but a filthy shell; Mrs. Strong, wife of our Maj. was appointed nurse by Mrs. Lander**, and she and I went about for weeks with rag in hand, overseeing and instructing in cleaning. We already had between 20 and 30 patients – and this, with getting things in order, kept us very busy.”15

The 20 or 30 initial patients were soon overtaken by a much larger number of wounded from the famed Battle of Battery Wagner.

Again from Esther Hill Hawks’ diary –“July18th! never to be forgotten day! After many days of anxious waiting the news came, “Prepare immediately to receive 500 wounded men,” indeed they were already at the dock! And before morning we had taken possession of the building where our first hospital was started… 150 of the brave boys from the 54th Mass. Col. Shaw’s Regt. Were brought to us and laid on blankets on the floor all mangled and ghastly. What a terrible sight it was! It was 36 hours since the awful struggle…and nothing had been done for them. We had no beds, and no means of building a fire, but the colored people came promptly to our aid and almost before we knew what we needed they brought us buckets full of nice broth and gruels, pitchers of lemonade, fruits cakes, vegetables indeed everything needed for the immediate wants of the men was furnished – not for one day but for many (Then too the Sanitary Com. Blessed us with its ready aid. Everything for our immediate wants was furnished and in 24 hours the poor fellows were lying with clean clothes and dressed wounds in comfortable beds, and we breathed freely again) before setting about creating a hospital: no one, unless they have had the experience can imagine the amount of work and worry needed in setting one of these vast military machines in motion! And in this case humanity demanded that the poor fellows who had fought so bravely, should be first attended to. The colored people still continued to supply delicacies and more substantial aid came from the citizens and Sanitary Com. (It was a busy time, and the amount of work done in the first 24 hours, by the two surgeons, and one sick woman is tiresome to remember! The only thing that sustained us was the patient endurance of those stricken heroes before us, with their ghastly wounds cheerful & courageous, many a poor fellow sighing that his right arm was shattered beyond hope of striking another blow for freedom!…”16

The August 1, 1863 issue of the Beaufort newspaper The Free South lists the names of 67 members of the 54th in Hospital #10.Elias Artist, G. Alexander, John Barker, Samuel Berry, John A. Boulden, W. Briggs, David Bronson, Thomas E. Burley, Thos. E. Buyers, Wm. Buyers, C. Charlton, Callhill Charlton, Jacob Christy, Charles Clark, James Cole, James Coleman, James Conkleton, Wesley Conkleton, Wm. Conkleton, Thomas Cooper, Anthony Dean, Samuel DeForrest, L. Delaney, G. Fisher, Eli Franklin, Joseph Gallas, Martin Gilman, Peter Glasby, P. Glastnally, Charles Goff, Benj. Granger, G.H. Hall, G. Harlbart, John Hedgepath, A. Hill, James Jackson, Sanford Jackson, John Johnson, Joseph Johnson, B. Krass, John L. King, W.R. Lee, John Lott, V.M. Mago, Edw. Mills, Wm. Milton, John Mogan, Samuel Moles, J.H. Montgomery, J.A. Palmer, Ned Pegrin, John Price, W.A. Rankins, Charles K. Reason, James Riley, George Rivers, G. Rust, John Shafter, B. Smith, Jr., B. Thompson, G. Thompson, Sam Tipton, H. Tucker, John Turner, George Washington, H. White, Chas. Whitney, Edward Williams, S. Winnis

From Esther Hill Hawks’ diary we get to know some of the men behind the names.“Many have died, several cases of gangrene have been provided for in tents: Two severe amputations today neither surviving but a few hours. One of these, a boy hardly 20 years old, Charley Reason, formerly a slave, but of late years resident in Syracuse NY., I have taken a great interest in; he is such a noble looking fellow, and so uncomplaining – so grateful when I bathe his head and face, as I sat by him holding his one poor hand! Oh yes! He said in reply to my question of why he came to war! I know what I am fighting for, only a few years ago I ran away from a man in Maryland who said he owned me and since then I’ve worked on a farm in Syracuse but as soon as the government would take me I came to fight, not for my country, I never had any, but to gain one[.]

“I find many of these men have been slaves, but by far the greater proportion were born and bred in the free north -- A few are from Canada. Some few well educated -- three graduates from Oberlin. They are intelligent, courteous, cheerful and kind, and I pity the humanity which, on close acquaintance with these men, still retains the unworthy prejudice against color!

"Three Krunkleton [sic] brothers, noble, stalwart men, lay side by side severely wounded! The fourth who had left home with them fell and was buried with his Col. at Fort Wagna [Battery Wagner...]

"One young man, Jonny Lott, one of my especial pets a handsome boy, a mere boy, who had come from the far west to bear his part of suffering, had his right arm shattered and his life was, for many days, despaired of, and in the long days of weary restlessness I learned the brave spirit of the boy well. He was well educated – had taught a term in a colored school[...]

"[T]he seventy under our care won golden opinions from us all by their patience in bearing the petty annoyances and deprivations to which all must be subjected – and during the two months that I went in and out among them no difficulties occurred which my presence and word could not settle. I endeavored with my whole heart, to make this dreary hospital life, as home-like as possible — and I was richly rewarded by their grateful thanks.”17

The hospital’s tenure as a place of compassionate care changed, however, by mid-September of that year when Dr. Charles Mead, formerly the Assistant Surgeon of the 112th New York Infantry was placed in charge. Esther Hill Hawks left the hospital at about the same time, returning in October and November as a teacher. She describes Dr. Mead as “a young, ineficient disipated negro-hating tyrant.” Embezzler of foods and clothing sent to the 54th Massachusetts from Boston, Dr. Mead was “most heartily hated by the men”…and “soon ran his course in the hospital, but not before almost every patient in it had served a few days in the jail for some trivial offense.”18

In November, Esther Hill Hawks left the hospital to join her husband, John Milton Hawks, recently promoted to Surgeon for the 3rd SC Regiment on Hilton Head Island. With her departure, her first hand account of life in Hospital #10 ends.

The Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House, though, continued to serve as Hospital #10 as Beaufort’s black troops continued to see battle. In January of 1864, the troops played a major role in the Battle of Olustee, Florida. Five months before the war’s end they served at the Battle of Honey Hill and on April 18, 1865, nine days after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, the Massachusetts 54th fought in the Battle of Boykins Mill. It was the last battle of the war in South Carolina thus bringing their service and the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House’s tenure as a hospital to an end.

*Later in the war two neighboring buildings – the H. M. Fuller House (where the University of South Carolina Performing Arts Building now stands) and the Beaufort College Building (in the Civil War era photo at left)– were also converted to hospitals and were known collectively with the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House as the Hospital #10 complex.

**A former actress and head of the Sanitary Commision in Beaufort

14. Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, the Port Royal Experiment, University of Georgia Press, Athens Georgia, 1964, page xi

15 The Diary of Esther Hill Hawks as cited by Gerald Swartz, A Woman Doctor’s Civil War, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC 1984, page 48

16Ibid,, page 50

17Ibid, page 51

18Ibid, page 54

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

From Slaves to Contraband

With the arrival of the fleet and the fall of Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard, the whites of Beaufort fled, leaving behind an enslaved population of 8,000 in town and on the neighboring Sea Islands.

Giving vent to years of silenced resentment and the joy of perceived sudden freedom, the black population responded with rampant looting and widespread destruction. Order was soon restored under Union occupation, however, over a year would pass before the government would recognize the former slaves as free with the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

Until then, the former slaves were considered contraband of war. Known simply as contraband, they had a limbo status of neither slave nor free, a status that reflected Northern political considerations. Politically, the war was proceeding poorly for the North. A threatened Washington was dependent on the continued neutrality of the border states – a neutrality that would have been jeopardized with emancipation.

The prolonged contraband status also reflected an underlying racial prejudice, as evidenced in the satirical drawings that ran in Harper’s Weekly immediately after the fall of Forts Walker and Beauregard (shown at left). Such drawings both revealed and fed the racial prejudice of the era.

Racial attitudes of the time led many whites to believe the former slaves incapable of functioning as free individuals and any thought of a future society where white and black lived together as equals was inconceivable.

As the North pondered possible ‘solutions’ such as the repatriation of blacks to Africa or the creation of colonies in Haiti, the former slaves remained contraband.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The 1861 Evacuation

By November 2, 1861, Confederate intelligence had determined that Commodore Samuel F. DuPont and his Union armada were headed for Port Royal. Residents were advised to evacuate. All across Beaufort the white population made hasty arrangements to flee inland to safety. Many took only a few necessities, expecting to return after a successful Southern defense of the harbor.

An American Family by Stephen Barnwell relates a poignant firsthand account from Anne Barnwell Walker, fifth daughter of John Gibbes Barnwell, of that last Sunday in Beaufort before the invasion.

“[The day was] beautiful beyond description. Our hearts were filled with patriotism and devotion while the organ pealed the beautiful hymn ‘God save the South.’ Dr. Walker* preached a sermon full of faith in their cause, reminding his flock ‘that God is nigh to all who call upon Him.’ He announced that he would ring the bells of the church the next day at noon and asked the heads of families ‘to gather their households together and hold family prayers’ (such as few neglected to do at least once every day in those far off times). We were subdued as we walked home, but we never dreamed of the fate before us.”12

Another firsthand account in An American Family comes from Anne Walker’s daughter Emily. She relates her memories of the anguishing last hours for the family at 705 Washington Street.“[I] went around to Grandma’s to see what they were going to do…

“Grandma was born in exile in Maryland when we were fighting our ancestors the English… Grandma was now eighty-two. She, Aunts Sarah and Emily decided on account of Grandma’s age they would leave at once. The coachman, Daddy Sam, was told to drive the carriage to the front door…The negroes made up a bed on a stretcher for Grandma, looking broken hearted, no talking by anyone except what was absolutely necessary. Grandma sat in a chair. Daddy Will [the butler] took it up on one side; Daddy Sam in the other. She was placed on the bed. Aunt Sarah, Aunt Emily, Maum Tenah got in, the door shut and they started on their long journey. Me? I was too excited to cry. I turned off for home little thinking that years would pass before I would see the old house again…”13

*Dr. Joseph Rogers Walker was the second husband of Mariana Smith, the eldest daughter of Marianna Gough Smith. He became pastor of St. Helena’s Church in 1823 and would serve until his retirement in 1878 with the exception of the five years of Federal occupation. A powerful religious influence in Beaufort, Dr. Walker was responsible for more than a score of young men entering the ministry, including his brother Dr. Edward Tabb Walker, who married Anne Bull Barnwell.

12The Story of an American Family, page 190

13Ibid, page 190

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Day of the Big Gun Shoot

October 29, 1861, the Union launched the largest US naval and amphibious expedition in its history – a force that would not be matched until the 20th c. Its mission was the taking of Port Royal, the finest, natural deep-water port on the East Coast south of New York. Guarded by Fort Walker on Hilton Head and Fort Beauregard at Bay Point, the port was vital to the Union both as a coaling station for blockade ships and as a strategic toehold in the South.

Also at stake was something less tangible, but equally critical, Northern morale. Deeply shaken by the defeat and heavy losses at Bull Run and an apparently stalled war effort, the North needed a victory. With Commodore Samuel Francis DuPont in command aboard the flagship USS Wabash, “one of the most important maritime engagements in the Civil War”11 was about to begin.

The morning of November 7th ushered in a new age in naval warfare. With the increased maneuverability afforded by steam power, naval warships for the first time had an advantage over fixed fortifications. In the four-hour siege that could be heard as far away as Lobeco, the USS Wabash alone fired 888 shots. In the battle that came to be known locally as the “Day of the Big Gun Shoot,” the forts proved no match for Union’s 157 guns. By 2:30 in the afternoon, both forts were abandoned and the North had its first significant victory in the war.

11The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, page 451

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Events of 1819 and 1825

Antebellum accounts describe the tremendous feasts that Beaufort planters regularly hosted for each other. The tables groaning with food and libation were testimony to their wealth, sea island abundance and a friendly competition among the planters as they tried with each feast to outdo each other.

At one point when the celebrations threatened to exceed even the planters’ standards for acceptable proportions, the Agricultural Society stepped in to institute a fine of 50 cents to discourage members from serving more than six dishes of meat at a single gathering.9

In a Beaufort accustomed to lavish celebrations, three would be remembered for surpassing all others. And John Gibbes Barnwell was fortunate enough to live to see and participate in all three -- the visit of President James Monroe in 1819, the Fourth of July Celebration of the same year and the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825.

In 1819, President Monroe was enroute to inspect the new territories of East and West Florida, recently acquired through the Adams-Onis Treaty with Spain. After crossing the Whale Branch River on the Port Royal Ferry, Monroe was met by virtually all of Beaufort’s white, adult male population on horseback. The presidential party (which included Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and South Carolina Governor John Geddes) was escorted by the welcoming crowd the six miles to town.

The spontaneous parade most likely followed what is now Boundary and Carteret Streets, taking the fifth president of the United States directly by the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House. It is easy to imagine the excitement generated by the procession and a not quite three-year- old John Gibbes Barnwell II and his older sisters watching from the grounds as it passed by.

The next day after an inspection tour of Fort Marion on Spanish Point, Monroe was given a banquet hosted by the “citizens of the College”10 which included John Gibbes Barnwell as a member of the Board. The evening was marked by numerous patriotic toasts and an outpouring of national and civic pride.

So great were the town’s emotions, they apparently could not be given full expression in one evening. So Beaufort was prompted to reprise the event two months later with the most memorable Fourth of July celebration in its history. Reportedly, a total of 31 toasts were made. With etiquette of the time dictating that an offered drink or toast was never refused, it is a wonder who among the celebrants was able to keep count. Unless it was John Gibbes Barnwell, for he is said to have found a singular way around the custom.

As the story goes on his wedding day, his friends offered him glass after glass of wine to celebrate, hoping to see John, who was known for moderation, for once inebriated. But much to their surprise, John continued to show no side effects, until it was discovered that he had been pouring the contents of each glass into his high cravat. He was soaked, but sober for his wedding.

The third high point for Beaufort, and certainly for John Gibbes Barnwell as well, was the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825. The town had declared the entire day a holiday in his honor. But weather and the tide delayed his arrival aboard the steamship SS Henry Shultz until 11:00 PM. Even his late arrival, though, could not deter the town from welcoming one of the most celebrated and beloved heroes of the American Revolution. Like Monroe, he was greeted by virtually the entire town. This time the town turned out with a spontaneous candlelight procession up Bay Street to a dress ball held in his honor.

9Theodore Rosengarten, Tombee, Portrait of a Cotton Planter, William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, page 11

10The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, page 291

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

John Gibbes Barnwell's Lands

A highly successful planter, John Gibbes Barnwell owned more than six plantations. His first and chief property was his 2000 acre plantation on Coosaw Island. He later inherited property on Parris Island and in the 1820s he purchased a plantation from Frenchman Georges Roupel known as The Ferry. It was named for its location next to the Port Royal Ferry at the northern tip of Port Royal Island overlooking the Whale Branch River. When the main house at The Ferry burned, John Gibbes Barnwell built a new one on the ruins of the old and named the property Roupelmonde. He later gave the plantation to his daughter Mary, possibly to serve as part of her dowry. She married Col. Middleton Stuart in 1829, the year following her father’s death.

At the time of his death, John Gibbes Barnwell properties also included a one-eigth share in the 4000 acre hunting preserve known today as Hunting Island and Retreat Plantation, both of which his son inherited. John Gibbes Barnwell II later sold Retreat Plantation to Rev. Edward T. Walker, the husband of his younger sister Ann Bull Barnwell.

After the death of his father, John Gibbes Barnwell II took over the management of the family’s properties, which included an additional two plantations on the mainland and 146 acres on Pigeon Point that his mother acquired in 1839.

The antebellum world of wealth and privilege based on the plantation system and slavery, however, would not last John Gibbes Barnwell II’s lifetime. On November 7, 1861 Union forces entered Port Royal Sound – their objective to take the finest, natural deep-water port south of New York. Fort Beauregard and Fort Walker soon fell, leaving Beaufort and the surrounding islands to the Union for the duration of the war.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

John Gibbes Barnwell

The eldest of five children and only surviving son of General John Barnwell, John Gibbes Barnwell was born February 1778, the year his father was first elected to the State Senate.

According to family lore, when he was only sixteen his father put his capabilities as a planter to a test on the General’s 2000-acre Coosaw Island plantation, promising his son the plantation if he proved successful.

He proved a more than competent planter and Coosaw Island soon became his. By the 1820s, his holdings included his principle plantation on Coosaw Island, part of Parris Island, the Retreat Plantation, a plantation on the northern end of Port Royal called Roupelmonde as well as two more plantations. He also bought the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House, a purchase that would keep the two-story tabby mansion in the Barnwell family until the turn of the century.

John Gibbes Barnwell along with (later General) Stephen Elliot, John Fripp, E.M. Capers and Dr. D.W. Jenkins also owned a small island off St. Helena Island that the men used as a hunting preserve. The practice was continued by their heirs, ultimately giving the island the name it has today -- Hunting Island. According to his hunting partner Stephen Elliot, John Gibbes Barnwell had his share of the Barnwell spirit. A daredevil, he is said to have made a practice of diving under water to pull alligators from their lairs.Also independent minded like so many of his family, John Gibbes Barnwell flouted the law by teaching a slave named Venture to read, write and do simple arithmetic eventually making him the sole manager of one of his plantations.

Like many of the Barnwells, John was tall, 6’2”, and possessed of the Barnwell family good looks, but unlike his father and Uncle Robert, he was not active politically. The Barnwell family’s interest in politics appears to have skipped generations, with Gen. John and Senator Robert emulating their grandfather Tuscarora Jack and John Gibbes Barnwell following in the footsteps of his grandfather Nathaniel. Like his grandfather, he devoted his energies more to his holdings. The only exception was during the War of 1812.

During the war, he served in the First Regiment of Militia in Beaufort, making the rank of Captain of Company B. John, like Beaufort, though, saw little action. There was a brief blockade of St. Helena Sound by two British armed brigs, the HMS Mosell and HMS Calabri, before a hurricane drove them out to sea, sinking one. At Sen. Robert Barnwell’s urging Fort Marion was built for the defense of Beaufort on Spanish Point at the site of Revolutionary War Fort Lyttelton. The greatest effect of the war was a boom economy brought on by the troops stationed in the town and the highest prices for sea island cotton for decades to come.

In addition to serving in the militia, John was also on the Board of Beaufort College and a vestryman for St. Helena’s Church. The positions he held, while not especially politically powerful, were indicative of someone of his wealth and family connections. They assured him (if not simply by his wealth and the Barnwell name) a prominent role in three of the most exciting events in the Beaufort in his lifetime: the visit of President James Monroe in 1819, the heady Fourth of July celebration of 1819 and the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825.

John Gibbes Barnwell by all appearances was blessed in his personal life as well. Like so many of the Barnwells, John married a first cousin, Sarah Bull daughter of General Stephen Bull and Anne Barnwell. Sarah was born December 18, 1782 in Maryland, where the family had been forced to seek safety during the Revolution. John and his wife Sarah had seven children all of whom lived to adulthood. They were:

Eliza Barnwell born 1807

Charlotte Bull Barnwell born 1810

Mary Howe Barnwell born 1812

Sarah Bull Barnwell born 1814

John Gibbes Barnwell born 1816

Anne Bull Barnwell born 1818

Emily Howe Barnwell born 1820

In addition to his own children, John was the guardian of his uncle Senator Robert Barnwell’s four younger children following the Senator’s death in 1814. They were:

Robert Woodward Barnwell born 1801

William Hazzard Wigg Barnwell born 1806

Mary Gibbes Barnwell born 1808

Esther Hutson Barnwell born 1809

The house at 705 Washington was no doubt again a center of youthful Barnwell activity.With the Captain’s death is 1828, his former ward and now son-in-law, Robert Woodward Barnwell became the guardian of John’s younger children. Robert, like his cousin Robert Barnwell Rhett, would in the ensuing decades become one of Beaufort’s leading public figures. A graduate of Beaufort College, Robert Woodward Barnwell continued his studies at Harvard. Elected to Phi Beta Kappa his junior year, he was valedictorian for the class of 1821, a class noted for the exceptional number of graduates who would later attain prominence in their respective fields – including Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was to remain a lifelong friend of Robert’s. Elected to the 21st and 22nd U.S. Congress and appointed interim US Senator in 1850, he was an early champion of Nullification. Originally opposed to secession, he changed his position after the election of Lincoln and was one of the framers of the Confederate Constitution. He declined Jefferson Davis’ offer of the position of Secretary of State for the Confederacy, but served in the Confederate Senate throughout its brief existence, representing South Carolina.

During his early career he was also elected 3rd President of South Carolina College and was responsible for significantly expanding its enrollment and facilities, which included the creation of a library that was considered one of the top two in the South, surpassing the libraries of Princeton and Columbia Universities.While his cousin and early law partner, Robert Barnwell Rhett, was known as a “fire eater,” Robert Woodward Barnwell was admired for his modesty, kindness and fine mind. Not the least of his accomplishments during his lifetime was his role in rearing his and wife Eliza’s thirteen children in additon to serving as guardian to his wife’s younger siblings upon the death of her father.

In the close knit extended Barnwell family, the two branches would be particularly intertwined, with Robert Woodward Barnwell and Eliza giving several of their children the same names as other family members. They were:

John Gibbes Barnwell born 1831 (named for Eliza’s father and brother)

William Hazzard Wigg Barnwell 1836 (named for Robert’s brother)

Sarah Bull Barnwell born in 1840 (named for Eliza’s mother and third sister)

Charlotte Bull Barnwell born 1848 (named for first Eliza’s sister)

Emily Howe Barnwell born 1850 (named for Eliza’s fifth and youngest sister)

Captain John Gibbes Barnwell’s son, (later Major) John Gibbes Barnwell followed the same practice, naming one son John Gibbes Barnwell in 1839 and another Robert Woodward Barnwell in 1849 – the intention of honoring family members ultimately creating a veritable genealogical Gordian Knot in the Barnwell family tree.

After Captain John’s death in 1828, his widow Sarah continued to live in their Beaufort home until the arrival of the Union armada in Port Royal Sound signaled the end of an era for Beaufort and the house at 705 Washington. At the age of 79 and infirm, the widow Sarah and daughters Sarah and Emily were part of the 1861 evacuation of Beaufort.Sarah died the following year while in exile in Walterboro. Four of her grandsons serving in the Beaufort Artillery escorted her body to Sheldon Churchyard where she was buried alongside her parents.

After the Civil War, her daughter Emily reportedly sold her diamond ring in order to have her mother reburied along side her husband in St. Helena’s Churchyard.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Yellow Fever

Yellow fever was the most deadly and feared of the ‘fevers’ to strike South Carolina. Outbreaks were almost an annual occurrence, with no fewer than 11 major epidemics between the turn of the 19th c. and the Civil War. The year Elizabeth Barnwell Gough contracted yellow fever and died an estimated one-sixth of the population of Beaufort succumbed to the disease.8

Throughout the country the fear was both so great and understanding of the disease so lacking that many stopped shaking hands and avoided passing close to houses where someone had died. Some even endeavored to remain upwind from all others they encountered. The belief that the disease was contagious resulted often in sufferers being sent to quarantine islands.

Not until the beginning of the 20th century would a mosquito, the Aedes aegypti, be identified as the carrier of the disease. Until then, medical authorities could only observe that there was a higher risk of outbreaks during the warmer months and near swamp or marsh areas. The generally accepted interpretation was that the higher incidence was due to unhealthy air.

Early treatment included bloodletting and large doses of calomel (a purgative and fungicide also known as mercurous chloride). One South Carolinian doctor practicing “mild” bloodletting took as much as 72 ounces of blood from yellow fever patients, drastically reducing the chances of recovery. Elizabeth at least may have escaped such treatment. Beaufort’s Dr. James Robert Verdier, whose residence is now known as Marshlands, is reported to have had a higher success rate than others in treating the disease, suggesting that he spurned the drastic measures of the day. But even the possibly forward thinking Verdier could do little against an epidemic of such proportions.

Elizabeth died October 10th, 1817 and is buried in St. Helena’s Churchyard.

8Joseph Waring, M.D., A Hstory of Medicine in South Carolina 1670-1825, South Carolina Medical Association, 1964, page 157

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Sunday, June 7, 2009

Robert Barnwell Rhett - The Father of Secession

Known as the “Father of Secession,” Robert Barnwell Rhett was born December 21st 1800 most probably in the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough house and was raised there by his grandmother until her death in 1817.

Like his grandmother and her grandfather before her, Robert Barnwell Rhett is known as one of Beaufort’s more colorful personalities. One of the earliest and most ardent and voices for States’ Rights and Nullification, he played a major role in eventually propelling South Carolina into the vanguard of the Secessionist Movement. One of the last of the Barnwell family to wield tremendous wealth and political influence, his single minded devotion to the cause helped to bring on a war that would end five generations of Barnwell reign.

Admitted to the bar in Charleston in 1822, he practiced law briefly with his cousin Robert Woodward Barnwell, before launching his high profile political career. In 1837, along with five brothers, he changed his last name from Smith to Rhett to honor his paternal great-great grandfather Colonel Rhett of Charles Town whose name had died out.His long political career included twelve years in Congress and chairmanship of the powerful Ways and Means Committee. He was a delegate to the Nullification Convention of 1832 and a US senator before resigning in 1852.

A powerful and compelling public speaker, he was known by his contemporaries as a “fire eater.” Praised for his honesty and high standards of conduct, he was alternately described as impulsive and rash – his colorful personality not unlike his grandmother’s.

The traits that made Robert Barnwell Rhett one of Beaufort’s most famous antebellum figures may well have been instilled at 705 Washington Street by a strict disciplinarian grandmother who once had been a fiery tempered, impulsive young woman.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Barnwell Brothers

During the Revolution Elizabeth’s three brothers John, Robert and Edward all served as officers. In a war where many withdrew or changed sides under pressure, all three brothers served steadfastlly on the patriot side. By the war’s end, John had reached the rank of Brigadier General; Robert had been promoted to Colonel and Edward, a lieutenant at only 18, had reached the rank of Lt. Colonel.

February 9th 1779, Robert and Edward fought in brother John’s troop in a battle on Port Royal Island, remembered now for the two British officers who were killed and buried in St. Helena’s churchyard at John’s direction, reportedly saying:

“We have shown the British we not only can best them in battle but that we can also give them a Christian burial.”sup>6

Robert was wounded 17 times in one battle and left for dead.

For more than a year, all three brothers were held on the British prison ship Pack Horse in Charleston Harbor. In 1781, when the ship left to transport its prisoners to Philadelphia, the brothers helped to commandeer the ship and guide it into patriot hands.

After the war, John and Robert served in numerous important political positions. John was elected to the SC Senate in 1782 and with the exception of 1788-1791 was a senator until his death in 1800. He was promoted to Major General of the 2nd Militia in 1799. Robert and John were both part of South Carolina’s delegation to ratify the Constitution. Robert was a US congressman and declined to stand for a virtually assured election as a US senator. He served on Beaufort’s first City Council and was Beaufort’s first intendant (mayor). Both were active in the founding of Beaufort College and served as vestrymen of St. Helena’s Church. During their lives, John or Robert served in (or was offered) every public position of power or influence in Beaufort.

Their power was further enhanced by their early involvement with the growing of sea island cotton. Before the war, indigo had been the staple crop of the area, but with the post-war loss of a British subsidy it proved no longer a profitable crop. Brothers John, Robert and Edward were among the first to recognize the potential of sea island cotton and so were among the first to reap its rewards.

The tremendous impact of cotton on the post-war economy and the fortunes of the Barnwell brothers is evident in a comparison of export figures over a single decade. Between the fall of 1789 and 1790, South Carolina exported 9,840 pounds of the long staple crop. Between the fall of 1800 and 1801, the amount had risen to 8,301,907 pounds.7 The Revolutionary War had made them heroes. Cotton made their names synonymous with wealth, power and influence. If Tuscarora Jack can be said to have laid the foundation of Beaufort, then John, Robert and Edward were responsible for its cornerstone.

6The Story of an American Family, page 33

7The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, page 281

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

The Revolutionary War

.jpg)

Caught in the middle of British and American forces vying for control of Charleston and Savannah, Beaufort suffered more than its share of turbulence and devastation during the Revolution. At one point, from July through September 1779, the British ship Vigilant was anchored in Beaufort Bay with its 24 cannon “ready to defend or destroy the town if necessary.”3 In 1780, Colonel Banastre Tarleton, in one of many troop plunderings, appropriated all of the horses from Beaufort and the Sea Islands as mounts for his “bloody legion.”

In addition to numerous regular troop actions was an almost endless round of raids and reprisals. For many of Beaufort’s families were bitterly divided over the war, with Elizabeth’s own family at the center of one of the bitterest feuds.

Her brothers John, Robert and Edward and the husband of her sister Anne, Gen. Stephen Bull, were all major players in Beaufort on the side of independence. On the side of the British was Elizabeth’s cousin Andrew DeVeaux, who was one of the most vengeful and ruthless in the war. He is said to have used the war as an opportunity to act on his personal hatred of John, Stephen and especially Robert. DeVeaux was responsible for carrying off of hundreds of their slaves and for numerous acts of destruction directed at his cousins personally, including the burning of Sheldon Church (which had been built largely with Bull family money) and Anne and Stephen’s plantation, Laurel Bay.

Even after regular forces had withdrawn from the area, guerrilla raids, murders, reprisals and a climate of lawlessness continued to plague Beaufort until the end of the war. In the chaos, travel and day-to-day commerce came to a virtual halt.The Reverend Archibald Simpson’s description of Beaufort immediately after the war is particularly telling:

“All is desolation…Every field, every plantation…No garden, no enclosure, no mulberry bush, no fruit trees, nothing but wild fennel, bushes, underwood, briars to be seen…a very ruinous habitation…“Every person keeps close to his plantation. Robberies and murders are often committed on public roads. The people that remain are peeled, pillaged and plundered.”4

“An entire generation had grown up between 1775 and 1783, and many knew only the uncertainty, violence and terror of a long war that in Beaufort… took a particularly vengeful turn.”5

In this climate, it is extremely unlikely that Elizabeth would have begun construction on her imposing home. More probably, she began building a new home and a new life for herself and her daughter when Beaufort (and the new country) began rebuilding in the latter half of the 1780s.

3Lawrence S. Rowland, Alexander Moore and George C. Rogers, Jr., The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume 1, 1514-1861, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC 1996, page 226

4Ibid, page 254

5Ibid, page 255

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Richard Gough

.jpg)

Like many of the early settlers in South Carolina, Richard Gough’s grandfather, John Gough, came to Charles Town from Barbados. His original land grant, dated October 12, 1709 included 3500 acres, part of the Barony of Thomas Colleton, in an area known as Goose Creek.

Born November 1750, Richard Gough was the son of John Gough’s second son Richard and wife Rachel Keating. Richard Sr. presumably enjoyed more than moderate success as a planter for his will directed that his son Richard be educated in England upon reaching the age of thirteen.

Why Elizabeth Barnwell’s family objected to her attachment to Richard Gough remains a cause of speculation. In social standing, financial status and political allegiance, Richard would have been an appropriate match for Elizabeth.Richard, like Elizabeth’s brothers, had aligned himself with the patriot cause even before the Revolution. Like Elizabeth’s brothers John, Robert and Edward, Richard served throughout the Revolution without wavering. Richard, also like the brothers, was a voice for moderation in the treatment of those who had been forced to change sides to protect their families or property during the war. Once again like them, he enjoyed the high regard of his peers for his brave and valuable service during the Revolution. Richard served as a Captain in the brigade of South Carolina’s most famous Revolutionary War hero, General Francis Marion, who was known as the “Swamp Fox” for his brilliant and elusive guerrilla tactics.

The most probable cause for the Barnwells’ objection to Richard Gough was his character. His spiteful and acrimonious nature is born out not just in the tales passed down, but also by his will of October 1791. He states in a clear attempt to prevent Elizabeth from securing funds rightfully due her:

“I give and bequeath unto Elizabeth Gough my Wife the Sum of Fifty pounds Sterling in lieu, compensation and final Extingishment of her Dower or Thirds and all and every other her rights, Titles, Claims, or demands whatever, of into, against or out of my Estate either real or Personal Item I give and bequeath unto Mary Ann Daughter of Elizabeth Gough my Wife, Fifty pounds and it is my particular Will, desire and Intention that the said Mary Ann shall not inherit any part or parts of my Estate either real or personal but the Fifty pounds given as above.”

The fact that the will was executed just two months prior to Marianna’s marriage together with his reference to “Mary Ann” as Elizabeth’s daughter, not his or “our” daughter prompts the inference that he was attempting to deny not just any financial claims Marianna would have (or her future husband would have on her behalf) but also any parental connection.

The will goes on to bequeath three slaves to a goddaughter and his cattle, horses and sheep to Keating Simons. The bulk of his sizable estate he gave to his mother for her lifetime and after her death to his godson Edward Simons, son of Keating Simons. Described in his will as his friend, Keating Simons was also the executor for Richard’s will and a cousin from Richard’s mother’s side of the family.Richard Gough died at his plantation in St. James Parish February 2, 1796.

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Saturday, June 6, 2009

Tuscarora Jack Barnwell

.jpg)

John Barnwell was by all accounts a heroic leader in battle, an adept statesman on both sides of the Atlantic and a visionary who helped secure the future of fledgling Beaufort. A skilled mapmaker in uncharted lands, John Barnwell literally and figuratively put Beaufort on the map. He also founded a family that would increasingly dominate Beaufort politically, socially and economically with each succeeding generation.

For more than 130 years after his death, Tuscarora Jack’s exceptional personality and spirit lived on in his descendents – as they, in turn, helped to mold the history of Beaufort.Born in Ireland to a well-connected, titled family of Barons, Baronets and Viscounts, Barnwell left for Charleston (then Charles Town) to seek his fortune around 1700. Founded only 30 years before, the once tenuous toehold in the New World had become a bustling port prospering from the cultivation of rice. Barnwell quickly established himself, serving first as Clerk of the Governor’s Council, later as Deputy Secretary of the Council and ultimately as Comptroller of the Province.

Governor Sir Nathaniel Johnson (for whom Barnwell would name his first son) was one of his early patrons. In the years leading up to 1709, Barnwell was favored with a series of land grants on Port Royal and vicinity for holdings totaling over 3,400 acres. His first contact with the area, where he would play an even more prominent role, was in 1703, when he was directed to map Port Royal Sound. Often a part of expeditions against the Spanish and French, Barnwell continued to map the region, eventually making “the great mother map of the American southeast from which all subsequent maps of the area were made.”2

In 1711, his extensive military experience led to his being given the command of a party of militia and 500 Indians (predominantly Yemassee) sent against the powerful Tuscarora Indians who had been raiding English settlements in what is now North Carolina. Outnumbered, under provisioned, and contending with both poor discipline and bitter winter conditions, the expedition under Barnwell’s leadership nevertheless managed to rout the Tuscarora. The success of his mission and his status as Carolina’s most experienced Indian fighter earned him the epithet -- Tuscarora Jack.

His trusted allies the Yemassee, however, in just four years would turn against the English. For years, Barnwell and Port Royal neighbor, planter and Indian agent, Thomas Nairne, had warned that the official exploitive policy toward the Indians was pushing them toward revolt.Their warnings proved correct on Good Friday 1715 when the Yemassee together with Creeks, Choctaws and Catawbas struck first at Pocotaligo Town. Two, perhaps three, colonists escaped the massacre, fleeing to Barnwell’s plantation.

Alerted to the uprising, 300 colonists fled to Beaufort and crowded aboard a smuggling ship that had been seized and detained in the harbor. Among the passengers was Barnwell’s ten year old son Nathaniel. Over 400 settlers, though, were killed in the uprising among them Thomas Nairne. Once again Tuscarora Jack was pressed into service to lead forces against the Indians, this time to drive his former allies the Yemassee into Florida.

In 1717, John Barnwell was also appointed to the first Board of Commissioners who were assigned the task of reforming Indian policy. He was also given the additional responsibility of directing the defense of the colony from the Stono River to St. Augustine.Although the Yemassee were ultimately routed, the uprising helped to fuel the colonists’ dissatisfaction with their governing authority, the Lord Proprietors. Their lack of support for the defense of the colony and self-interested rule led the colonists to petition for direct rule by the crown. The emissary deemed to have the requisite expertise and experience to plead their case was Colonel John Barnwell.

Arriving in London in 1720, he met with the Board of Trade and Lords Justices and successfully argued for transfer of power over the Carolinas to the King. His second mission was to propose that a string of defensive forts be built along the southern frontier. The financially conservative Lords Justices approved the building of only one, on the Altamaha River. On returning to the Carolinas, Barnwell oversaw its construction. Named Fort King George, it was the first permanent English presence in Georgia.A member of the assembly from 1717 until his death in 1724, Barnwell also served as Justice of the Peace for Granville County and commander of the county militia.

A widower at the time of his death, he left two sons, six daughters and an estate of over 6,500 acres.A founding father of Beaufort, he was also the patriarch of a prolific family that prospered, married well and carried on his legacy of public service to become one of the most powerful of Beaufort families.

For more than 130 years after his death, Tuscarora Jack’s exceptional personality and spirit lived on in his descendents – as they, in turn, helped to mold the history of Beaufort.Born in Ireland to a well-connected, titled family of Barons, Baronets and Viscounts, Barnwell left for Charleston (then Charles Town) to seek his fortune around 1700. Founded only 30 years before, the once tenuous toehold in the New World had become a bustling port prospering from the cultivation of rice. Barnwell quickly established himself, serving first as Clerk of the Governor’s Council, later as Deputy Secretary of the Council and ultimately as Comptroller of the Province.

Governor Sir Nathaniel Johnson (for whom Barnwell would name his first son) was one of his early patrons. In the years leading up to 1709, Barnwell was favored with a series of land grants on Port Royal and vicinity for holdings totaling over 3,400 acres. His first contact with the area, where he would play an even more prominent role, was in 1703, when he was directed to map Port Royal Sound. Often a part of expeditions against the Spanish and French, Barnwell continued to map the region, eventually making “the great mother map of the American southeast from which all subsequent maps of the area were made.”2

In 1711, his extensive military experience led to his being given the command of a party of militia and 500 Indians (predominantly Yemassee) sent against the powerful Tuscarora Indians who had been raiding English settlements in what is now North Carolina. Outnumbered, under provisioned, and contending with both poor discipline and bitter winter conditions, the expedition under Barnwell’s leadership nevertheless managed to rout the Tuscarora. The success of his mission and his status as Carolina’s most experienced Indian fighter earned him the epithet -- Tuscarora Jack.

His trusted allies the Yemassee, however, in just four years would turn against the English. For years, Barnwell and Port Royal neighbor, planter and Indian agent, Thomas Nairne, had warned that the official exploitive policy toward the Indians was pushing them toward revolt.Their warnings proved correct on Good Friday 1715 when the Yemassee together with Creeks, Choctaws and Catawbas struck first at Pocotaligo Town. Two, perhaps three, colonists escaped the massacre, fleeing to Barnwell’s plantation.

Alerted to the uprising, 300 colonists fled to Beaufort and crowded aboard a smuggling ship that had been seized and detained in the harbor. Among the passengers was Barnwell’s ten year old son Nathaniel. Over 400 settlers, though, were killed in the uprising among them Thomas Nairne. Once again Tuscarora Jack was pressed into service to lead forces against the Indians, this time to drive his former allies the Yemassee into Florida.

In 1717, John Barnwell was also appointed to the first Board of Commissioners who were assigned the task of reforming Indian policy. He was also given the additional responsibility of directing the defense of the colony from the Stono River to St. Augustine.Although the Yemassee were ultimately routed, the uprising helped to fuel the colonists’ dissatisfaction with their governing authority, the Lord Proprietors. Their lack of support for the defense of the colony and self-interested rule led the colonists to petition for direct rule by the crown. The emissary deemed to have the requisite expertise and experience to plead their case was Colonel John Barnwell.

Arriving in London in 1720, he met with the Board of Trade and Lords Justices and successfully argued for transfer of power over the Carolinas to the King. His second mission was to propose that a string of defensive forts be built along the southern frontier. The financially conservative Lords Justices approved the building of only one, on the Altamaha River. On returning to the Carolinas, Barnwell oversaw its construction. Named Fort King George, it was the first permanent English presence in Georgia.A member of the assembly from 1717 until his death in 1724, Barnwell also served as Justice of the Peace for Granville County and commander of the county militia.

A widower at the time of his death, he left two sons, six daughters and an estate of over 6,500 acres.A founding father of Beaufort, he was also the patriarch of a prolific family that prospered, married well and carried on his legacy of public service to become one of the most powerful of Beaufort families.

2Stephen Barnwell, The Story of an American Family, Marquette, 1969, page 5

Please note that the material in this blog is copyrighted. It is not to be reproduced without my specific written permission.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Elizabeth Barnwell Gough

For over 200 years, the hopes, struggles, triumphs and defeats of Beaufort, South Carolina have been played out within the walls of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House. An ill-fated romance, Revolutionary War heroes, leaders of a young nation, architects of its near demise in civil war, heroes on the side of the Union, pioneering women for women's rights, and members of the infamous Ku Klux Klan are all part of the home’s history.

It is a history as richly patina-ed as the tabby walls of its exterior. Extraordinary people came, lived and died here. Ordinary people have added to its history as well. There were people of great wealth and people who struggled with economic hardships. There were people who helped shape their eras and people whose lives were shaped by their times. Their stories tell the history of Beaufort and a much larger one that I will begin to share with you in exerpts from my research and writing for the owners of this remarkable home.

Traditionally, the history of the Elizabeth Barnwell Gough House begins in 1775 with the death of Elizabeth’s father Nathaniel Barnwell. The eldest son of Tuscarora Jack Barnwell, Nathaniel had amassed a sizable fortune, 1600 pounds of which he left to his daughter Elizabeth. The legacy provided for her lifetime support and for her daughter’s until Marianna’s marriage in 1791. The legacy also enabled Elizabeth to build one of Beaufort’s grandest and most beautiful homes.

But in a broader sense, the history of the Elizabeth Barnwell House begins long before the legacy or the home’s construction.

It can be argued that the history of the house begins even before Elizabeth’s birth with the remarkable life and achievements of her grandfather, Tuscarora Jack Barnwell. (More about Tuscarora Jack in my next blog.) Though he died 29 years before her birth, he left a legacy of bold action and independent spirit that shaped the character of the Barnwell family and undoubtedly played a large part in making Elizabeth who she was, the choices she made in life and even in the commanding presence of her home.